The Institute for the Humanities recently began offering a series of small grants (GTC+Faculty-Student Networking Grants) to support the GTC+ Networking requirement. These grants provide a stipend for graduate students who are working on larger projects with faculty members, in order to compensate the graduate students for their time. I was fortunate enough to receive the first of these grants to work with Professor Karla Mallette of the Departments of Italian and Near Eastern Studies to develop a digital timeline project for her Italian 240 course, “The Italian Mafia.”

To provide a little background on our project, I was not helping teach this course(there was no GSI for the course) but Professor Mallette was looking for someone to help her develop effective ways to use digital media in her course.When Professor Mallette and I first began discussing this project, she had already consulted with Theresa Braunschneider, CRLT Assistant Director. The course syllabus was largely designed, including detailed and thoughtful learning objectives, but she was not sure about the precise form that the students’ timeline project would take. This was the aspect of the course that we collaborated on. This is the assignment, as it appeared on the syllabus:

Timeline: You will work in teams to summarize the life and times of a specific historical figure. This will be a group assignment for two reasons: because there is too much information for one person to process; and because that’s how mafia crimes are investigated and prosecuted.

As you can see, this was designed as a group project in order to divide up the workload (in its final form, there were 19 people and 5 wars or other historical events to be included on the timeline) as well as to demonstrate the ways that mafia investigators worked. We discussed this in our first meeting, as we worked to determine what the best way to structure the assignment might be. Professor Mallette had developed the following course objectives before we even began working on how to develop this timeline project:

- Explain the socio-economic role that the mafia plays in Sicily and the major changes in the nature of mafia crimes and mafia businesses between 1860 and the present day

- Understand the history of the mafia in relation to contemporary events in Italian history and the history of southern Italy in particular; understand the history of the American mafia in relation to the history of American immigration and the Italian American experience in particular

- Distinguish between the mafia and other non-state actors: terrorist groups; secret societies (e.g. the Blessed Paulists or Masons); charity organizations and NGOs

- Identify the kind of evidence that can be used to prosecute mafia crimes – and understand why this evidence can be very hard to gather and to present in court

- Summarize and assess arguments that the mafia is a benevolent organization whose aim is to protect a population under-served by the state

By focusing on these learning objectives that she had in mind for the class (particularly #4), we determined that the rationale for a large-scale collaborative assignment like this was fundamentally tied to one of her main goals for the class. It was important to Professor Mallette to resist the impulse (which, I have to admit, I displayed in our meeting and which I think she rightly anticipated in her students) to glorify the members of the mafia. By focusing on the evidence used in mafia prosecutions and the difficulty of obtaining that evidence, we hoped to shift the focus away from glorifying and romanticizing the mafia actors. The question was how to effectively do this with the assignment.

Assuming a class full of students who would very likely be drawing on mafia movies for most of their prior knowledge of the Italian mafia (and who may well have signed up for the course because of those movies), we discussed potential ways to subtly shift the focus onto the investigators. The most natural way to do this seemed to be to align the students with the investigators. By casting them not as project teammates working on an assigned group project, but rather as a team of investigators working to gather relevant information about someone with mafia connections, we could (hopefully) shift student mentalities away from The Godfather (1972) and towards an Untouchables (1987) state of mind.

Conclusions

As Professor Mallette and I corresponded about this project and went through a process of trial and error, it became clear that there would be a lot of opportunities for learning on our end as we tweak and support it throughout the semester. Nonetheless, this project was a fantastic opportunity for me to apply many of the different resources and strategies that I have been learning about as I pursue the GTC+ certification. As graduate students, we often teach courses that are fully (or mostly) designed in advance. It was an illuminating and educational experience to be able to work with a professor to craft a course assignment. Being part of the planning process gave me the opportunity to implement some of the digital technology tools for which I have only had hypothetical applications in the past. I look forward to building off of what I learned here when I have the chance to design my own courses in the future.

For more details about how this project unfolded, complete with lots of trial and error and exciting screenshots, please continue reading below!

Choosing a Platform

With our goals in mind, the biggest concern was picking a program that was best suited to this project. There are several options for timeline software (Timeglider, Tiki-Toki, TimeToast, myHistro and plenty more), and Professor Mallette mentioned the Wiki functionality in our LMS, but neither of those options was a perfect fit. We wanted a way to allow students to work more collaboratively while still allowing professorial control over content. At the same time, the major figures that the students would be researching were not evenly spread out over time. Many of the timeline programs are designed to allow a certain degree of flexibility, but they are fundamentally designed to show a linear, chronological progression. Instead, we had a list of major figures whose interactions often constituted complex strings of causes and events. Further, those interactions tended to cluster around major events in Italian (and Italian-American) history, most of which were major wars and mafia investigations and prosecutions. As such, I suggested that another platform might be better, and we could customize it as we needed.

A platform that I have been experimenting with lately is Padlet. It seemed like it might offer the sort of visual/spatial and collaborative components that we needed. Professor Mallette sent me the information for the assignments, and I mocked up a sample website to show her the functionality that Padlet has.Another option I had considered was Prezi (because of the non-linear use of space that it allows for), but Professor Mallette was pleased with the Padlet sample,so it was time to get to work with the actual course project!

Creating the Timeline

Padlet has a wide range of things that it can accommodate. You can read about some of the other uses of it on their website, or (the way I was introduced to Padlet and an option that I highly recommend) through a CRLT seminar or through a Teaching with Technology consultation. For our purposes for this project, the important part was that it is highly customizable and allows for a great deal of creative, collaborative work while still allowing for oversight and moderation.

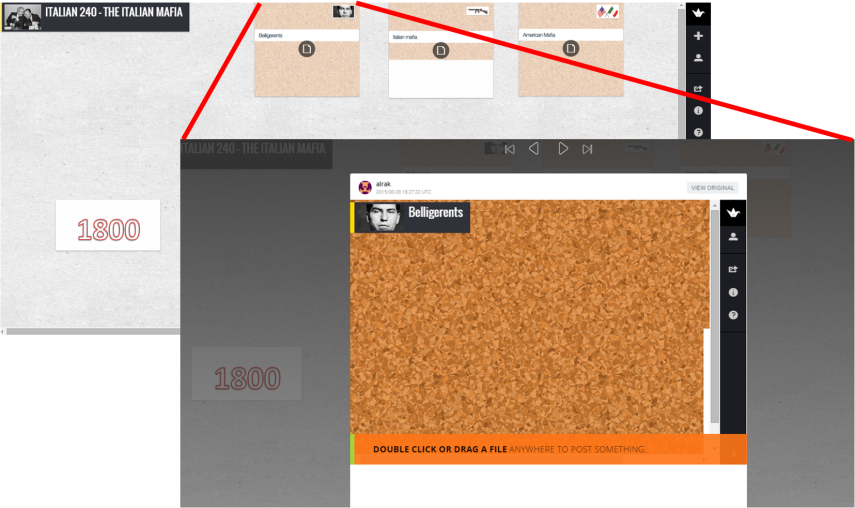

I set up a basic home page with date markers to structure the timeline. In addition to that, Professor Mallette and I added a series of pages that were more thematic groupings—Belligerents, Italian Mafia, and American Mafia. As you can see, if you click on any of these pages (which can be created by anyone, not just the instructor), it pops up a new, embedded padlet. So a student who researched a member of the American Mafia whose career peaked in the 1930s could create a page with all of the relevant content (videos, images, text, etc.) and then drag and drop that page into the timeline between 1900 and 1950 and also onto the American Mafia page. This way, the content can be access chronologically or through a more thematic connection. Further, students can arrange the padlets on the American Mafia page to indicate different sorts of connections between them and to combine their respective research in a way that draws out the interactions between historical figures rather than just a chronological relationship. Also, as you can see in this sample page,the format is vaguely reminiscent of the sort of bulletin board an investigator might use to spatially connect evidence about a perpetrator.

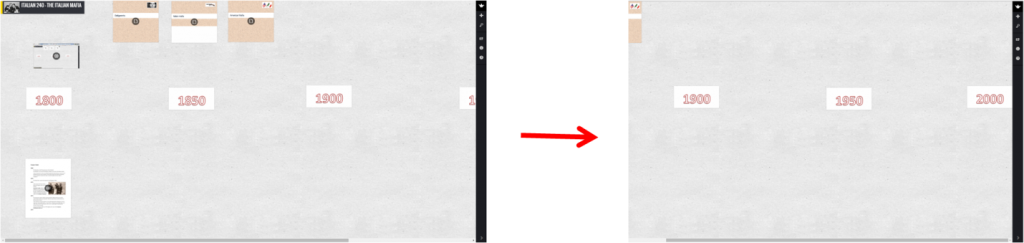

In addition to facilitating this sort of collaborative work and a more dynamic way of understanding historical interactions, the project design we used also allows students a great deal of creative flexibility. Padlets can expand indefinitely (see image) and you can customize a page in any number of ways (visually, spatially) and include a wide range of media. As such, students have the opportunity to add a more personal, creative element to scholarly research—something that is not often a high priority in university courses.

One of the reasons I chose this program is that its size can expand indefinitely, horizontally and vertically. This means that the platform itself will not limit the amount of information that can be added. You can simply move items farther to the side or down in order to create more space, which is ideal for a timeline which might need to expand to accommodate more content in a certain time range.

Security and Moderation

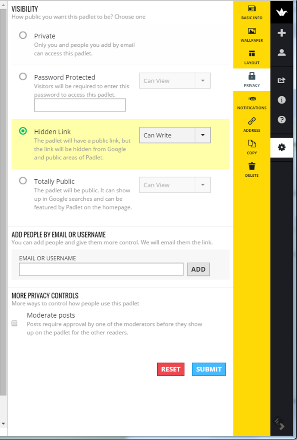

Finally, it was important to know that there would be safeguards in place so that the students’ work was secure and there was no potential for any sort of abuse. As you can see below, this allows the page’s creator to limit who can see a Padlet (pads can be either private, password protected, hidden, or totally public), and there are options to require post moderation as well.

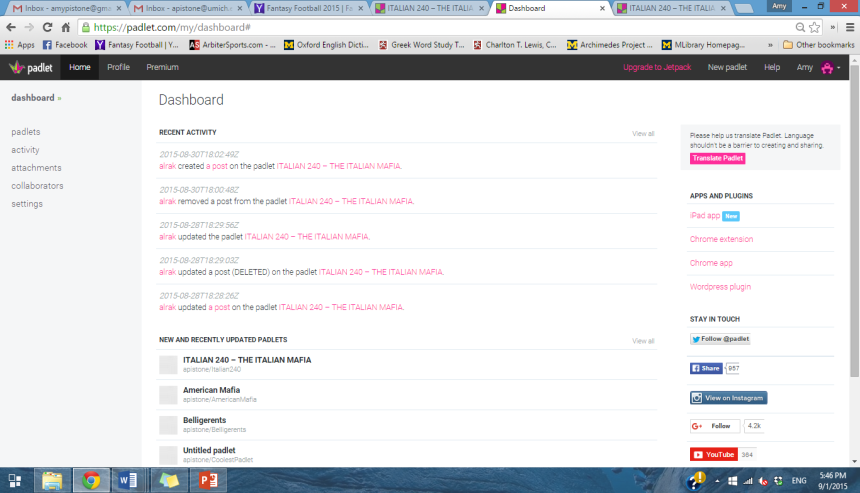

Finally, there is a log of all changes that anyone makes on a page, which allows the instructor to monitor student work and make sure that there are no problems.

Teaching the Technology

Sample page that I created via Screencast while talking students through all of the steps I was taking.

This is not a course on using new websites, so it was important to Professor Mallette and I that the technological barrier to entry be very low. For the most part, Padlet is an intuitive, user-friendly program, but only a portion of the Padlet options would be relevant for students, so it would be a waste of their time to invest a great deal of energy in learning everything Padlet could do. Instead,I made a series of three introductory videos (using Jing and Screencast) in which I walked the students through the things they would need to do for the course assignment. By watching a series of three short videos (Part 1: Intro to Padlet; Part 2: Making your own page; and Part 3: Adding your page to the main page), students could see me create,edit, and link together sample pages and content.

The goal was that students should be equipped to use and navigate the program and add and modify their assigned pages. This way, Professor Mallette would not need to use class time to go over any technical instruction that the students might need.

Screenshot of a Jing screencast, which I can then add directly to the Padlet page as an embedded video, simply by dragging and dropping it. This can be used for instructions and tutorials, as I did here, or a student could choose to make their own short video as part of their research and include it directly onto their page.