We need physicists. We want engineers. We want people to go to grad school and be able to afford it…

One problem america doesn’t have is a glut of scientists. We treat them like they’re getting philosophy doctorates.

The assumption here is that it would be fine to go after the philosophy PhDs. I assume that things like English and History and the rest of the humanities are sort of lumped in there. From what I’ve seen, the discussion around this terrible tax bill’s impact on higher ed has focused largely on the impact to STEM fields, because that’s an easy sell. Who wants to argue with the idea that we need to strengthen American STEM education? STEM is, from a marketing standpoint, uncontroversial. It’s a lot harder to fight for the humanities PhD students — no hit musicals feature a song about “What do you do, with a BA in Chemical Engineering?” The humanities have been an easy punching bag for a long time now, for a variety of mostly invalid reasons. So this debate has centered on the people we all agree shouldn’t be punished by Congress.

Because I’ve seen less about the humanities PhD experience, I thought it was worth sharing. In some ways, the finances come out about the same as for a STEM grad student. Here’s one comparison of the before and after costs:

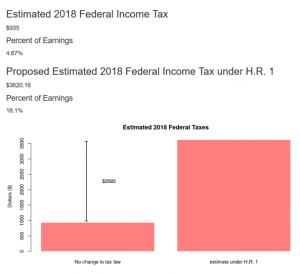

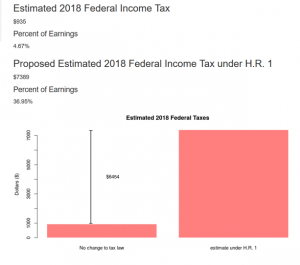

I punched the numbers into this tax calculator (I don’t offhand know how precise or accurate this is) and came up with these values for a University of Michigan graduate student, based on a 20k stipend (depending on residency status):

|

|

|

That’s a difference of $2,600 – $6,400. So, how big a deal is that?

Well, some departments (I was lucky to be in one of them) have extra money available for summer funding or emergency situations. But other departments at Michigan didn’t. And Michigan is better funded than a lot of Universities. As a grad student, I didn’t have to compete for funding with my classmates — we were accepted with a certain amount of guaranteed funding, between fellowship and teaching. And Michigan grad students are unionized, and have comparatively wonderful health insurance (thanks, GEO!). And there was money available from our department and the graduate school for travel to conferences and things. So I’m speaking from a very very privileged place.

We taught c. 20 hours a week, and were doing research with the rest of our time, which left very little time for a part-time job, though I and almost all the other graduate students I know picked up at least some part-time work on the side during graduate school. Even with part-time work, we’re still barely scraping by. Our stipends covered modest room and board just fine in Ann Arbor, but flights home were always tight. Catastrophic medical bills were less of a threat than if we didn’t have such good health insurance, but even the co-pay for things like mental health care added up. Major car expenses would absolutely wreck anyone’s grad student budget. If you needed to support anyone besides yourself, you were going to be on a very tight budget.

This system is already skewed heavily toward people don’t need to worry about money (which is one of many reasons academia is still struggling to increase diversity). If you didn’t have family members you could ask to help cover the gaps, you were left looking at loans, mounting credit card debt, or just doing without. And let me repeat, this is the best possible scenario. We barely made ends meet in the absolute best scenario. Many many graduate students are eligible for SNAP benefits. Others have to take out loans that they have no hope of ever repaying, because a humanities PhD means (for the most part) that you want to go into some sort of teaching or policy work. Those jobs aren’t handing out the pay-off-200k-of-student-debt sort of paychecks.

So what, you might ask? If you’re asking this, you probably aren’t the sort of person who is particularly receptive to arguments about a universal basic income or who thinks that wealth inequality is intrinsically a problem. “If it’s so bad, don’t go to graduate school in the humanities! Get a real job!” you might say.

Leaving aside the importance of the humanities and the advancement of knowledge (though one could certainly talk about the inherent societal risks of scientific and technological advancements without grounding what we do in history and ethics — another time!), gutting graduate school will make higher education as a whole a less diverse and equitable. Not only will graduate school only be available to the independently wealthy (which will ensure that the faculty of the future is drawn only from the socioeconomically elite, and we will undo any progress we’ve made at increasing diversity in the professoriate), BUT it will almost certainly mean that undergraduate education will become less accessible. Humanities PhDs are doing an incredible amount of the instruction at large universities. Without very very cheap graduate student labor, I can only see a couple options — either fewer students can take classes, the classes will shift more completely toward large lecture courses with no discussion (where the real learning happens), or more contingent faculty will be hired into deeply exploitative positions. Nothing about recent trends in higher education suggests that more tenure lines would be opened up, so the quality of undergraduate education would decrease across the board.

To some extent, argue with whatever arguments you think will convince people. The stakes are too high for me to really think we need some ideological purity about exactly why this tax bill is a terrible idea. But at the very least, don’t throw the humanities graduate students under the bus. This tax bill would be catastrophic for all graduate students across all disciplines, and all of their plights are worth fighting for.

no replies