Charts and a full set of my student evaluations are available here, if you are interested in a more quantitative overview of my teaching. What I would like to provide here is something somewhat different, and I have two cases studies I would like to present here. The first is a time that I struggled as an instructor and needed to find ways to improve my teaching, whereas the second (saving the best for last!) is a reflection on how I developed over the course of my time teaching in graduate school.

Two Case Studies

- It’s All Latin to Me: Challenges and Adjustments in Teaching Elementary Latin

- Great Books: A Great Story in Two Parts

It’s All Latin to Me!

In my second year of teaching at the University of Michigan, I taught Latin 101. Languages, as many people have learned first-hand, can be very challenging to teach, even in the best of circumstances. To add to the challenge, there can be a certain reluctance or resistance (even resentment?) among students when they are required by the University to meet a language requirement.

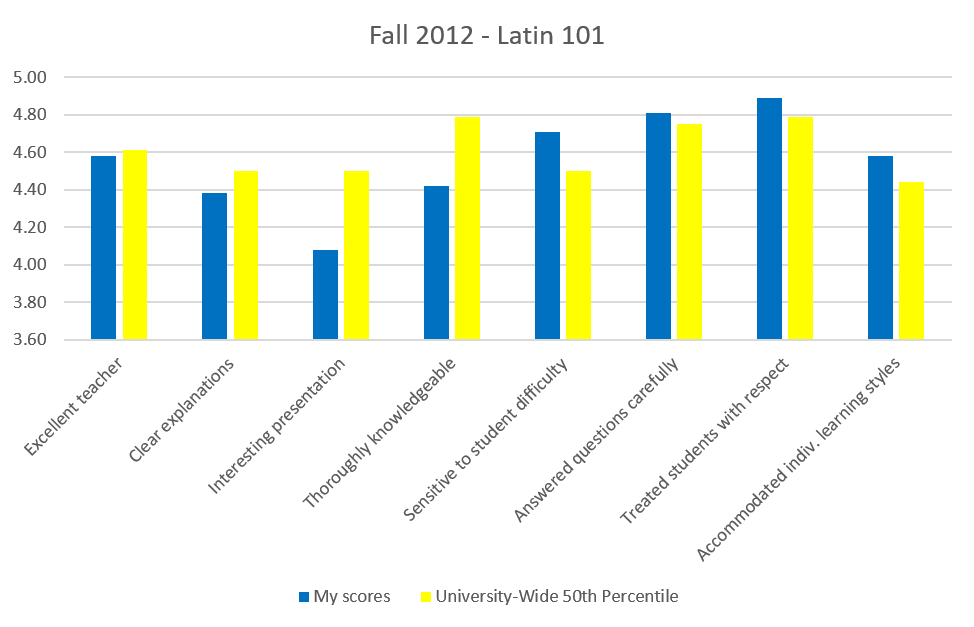

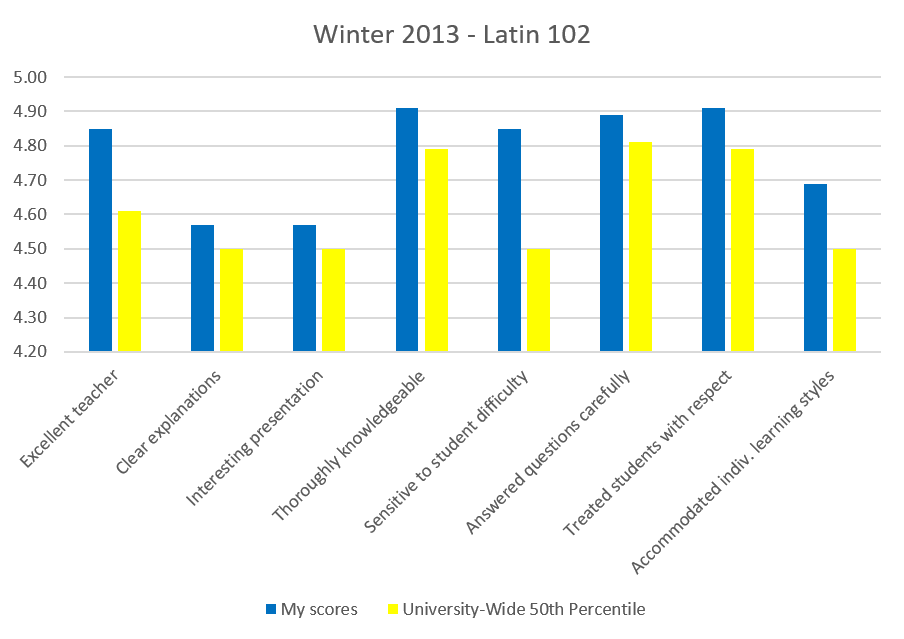

That being said, I was excited to teach Latin and poured my heart into the class. This was my first opportunity to be the primary instructor for a course and I was looking forward to the experience. Looking back on my experience, I have very warm, positive feelings about that class—they were great students who really tried hard to master a difficult language. What I did not immediately remember, until I was looking through my evaluations and my old records from the class, is how much learning I also had to do that semester. Though evaluation scores aren’t a perfect tool, I also don’t think it’s a coincidence that my evaluation scores were the lowest for that Latin 101 semester (Fall 2012, the only semester my scores have ever been below the university-wide median for scores).

Where I could relive my own struggles and improvement was in my students’ comments. Because I had developed so many better approaches by the end of Latin 102, I think my memory re-wrote that first semester a bit, as though I’d been a great language instructor since Day 1. When I thought harder, though, it’s clear that I wasn’t. I had learned Latin in an intensive 1-semester course as an undergraduate, and I had learned Latin after I already knew Greek, so I had a comparable framework I could use to anchor this new language. My students were learning about things like genitive cases and subjunctive verbs for the first time, and I was not immediately providing them with the best instruction to help them learn.

It was only midway through their first semester that I started making extra resources for my students, such as this flow-chart to help walk them through the best ways to approach a noun, after I noticed that they could translate sentences if I was there to prompt them, but they weren’t learning to ask themselves the right questions to get to an accurate translation.

I started talking to my cohort-mates and fellow Latin 101 instructors (Jacqui Stimson and Nicholas Geller) about where our students were having the most trouble, and we began working together to produce sample sentences which targeted the specific areas where our students needed more practice. This allowed for a division of labor, so none of us had to produce all of the extra content, but it also allowed us to troubleshoot our teaching. Did my students struggle with deponent verbs because the content was inherently difficult or because I wasn’t teaching it very well? By comparing notes, we could use each other as resources to learn to teach better.

My evaluation comments reflect this improvement. They also, incidentally, reflect my deep love of outdated pop culture references and internet memes. But mostly, they reflect the steady improvement. Just as my students were working hard to improve their Latin, I was working hard to improve my Latin instruction. And they noticed!

“I especially enjoyed the meme-filled emails and (occasionally outdated) pop culture references. Overall, good. I liked the clearer outlines of the material we were going to cover toward the end of the class.” (emphasis mine)

“Amy was born to teach. She is legitimately the best teacher I have had, not only here at U of M, but throughout my entire high school career as well.”

“Amy Pistone is a wonderful teacher. I really liked her way of teaching. Being a specialist in Greek, she is a really good Latin instructor, so, probably in Greek she is an amazing teacher. She understands perfectly how to make the best of the system used in the Classics department, which I like too. It is not easy to help students to start learning Latin, we had many difficulties at the beginning, but Amy has been able to help us. She has been also trying to identify our problems and concerns from the beginning to the last day, moreover, I think she has learned during the process how to teach us even better. What I most like of her way of teaching is that her personal goal seems to be to teach us not only Latin, if not how to think better.” (emphasis mine)

In Latin 102, I retained these improvements I had made to my teaching while also incorporating some new aspects. I continued to work closely with my fellow instructor, Jacqui, both to improve our teaching strategies and to add more fun aspects to class. Our students consistently asked for more Roman cultural content in class, though there was limited time to cover Roman culture in a language course. We added Roman trading cards (the students would receive two new cards each Friday in one of three categories—writers, political/military figures, or mythological figures). One of my favorite classes was Valentine’s Day, when my class celebrated the Lupercalia with Lupercalentines and shaggy fabric strips meant to be leather straps or whips, and each of the students wrote a poem about love (with a few selections from Catullus and Propertius as samples, so they had a sense of how loving/unloving Latin elegy could be!).

The biggest thing that I added to my own teaching was targeted mid-class (anonymous) surveys to help teach the students in the way that they could learn the best. Rather than just asking for generic feedback, I had learned what sorts of questions would be most useful for me, in improving my teaching, and so the surveys I sent my students had very specific questions with very specific answer choices. This allowed me to check in regularly and find out what sorts of homework assignments they found most useful and what sorts of class activities they preferred. Even when I could not accommodate everyone’s preferences, I made sure to at least discuss the survey results with my students so they knew that I cared about their input and that I hadn’t just ignored their feedback, even if I wasn’t able to incorporate it into my teaching.

And the happy ending to this story is that the students (many of whom were in both my Latin 101 and 102 classes) noticed and appreciated my teaching and the changes and improvement that I made:

“I LOVE AMY. She’s such a great person, so friendly to all the students, very patient with any difficulties or confusion, and just has such a gem of a personality. We can all tell that she’s honestly enthusiastic about both Latin and having the opportunity to teach us. She places an emphasis on personal attention, which is wonderful in such a large school. The only thing I would recommend changing is when we’re learning new material, once she covers the explanation in the book, if we could do one or two of the exercise sentences together just to all get a better handle on exactly the thought process to use to approach the problem, it would help us use our time much more productive when working separately in class rather than floundering through the new ideas…But overall, Amy is a really truly fantastic teacher!”

“She’s already doing a fantastic job. She is very accommodating and more than willing to help students outside of class.”

“I think Amy was incredible and I honestly cannot think of any way she can improve. I can say that she is truly the best teacher I have ever had.”

“Amy did a great job at incorporating all of our suggestions throughout the year and continually asking how she could improve the course, which was extremely helpful and leaves nothing else needing to change.”

“More Roman flash cards and pop culture references. Definitely. :)”

“The English to Latin love poem composition was a lot of fun! It really encouraged us to be creative while using our more advanced constructions and vocabulary, as well as think about the subject matter in a different way. We should have more assignments like this!”

Great Books: A Great Story in Two Parts

Great Books is a writing-intensive course taught in the Honors College at Michigan. I taught Great Books two successive Fall semesters (2014 and 2015), and Great Books is similar in many ways to Classical Civilization 101 (CC101), the first class I taught at Michigan (in Fall 2011). Looking at these three semesters allows me to reflect nicely on a lot of the choices that I have made in my teaching career thus far.

There are two or three major differences between CC101 and Great Books. The first is that even though both classes involve a large amount of revised writing, CC101 is much more strictly structured as a writing class—there are mandatory writing worksheets on things like thesis statements and using quotations in an essay. In the Honors College, things are somewhat more relaxed and there is not as rigid a structure. This leads to the second major difference: there is significantly more autonomy for section instructors in Great Books. Both the students and the graduate student instructors have to go through an application process to be a part of the Honors College, but the trade-off is that the instructors have a lot more discretion in terms of what and how they want to teach in their section. The final major difference is the content of the two classes: CC101 is an Intro to Greek civilization course, whereas Great Books is focused almost entirely on Greek literature.

With the benefit of hindsight, I can thoughtfully look back at these different classes and take a lot of lessons away from these teaching experiences.

Literature vs. Civilization Classes: these teaching experiences showed me what a difference there is between these two types of classes. Though there is a lot of overlap in the texts that show up in each type of classes, there is an important difference in how those texts are taught. When you read the Iliad, how important is it for the students to understand what historical and archaeological evidence there is for an actual Trojan War? What about oral poetry and the way that the text of the Iliad changed over centuries before it was written down in a definitive form? Do students need to read all 24 books of the Iliad or can they skip the fight scenes in the battle books, and skip up to the parts about Achilles? Does it matter if there was one Homer or “Homer” is the product of many bards? Were Achilles and Patroclus lovers? How realistic are the descriptions of warfare? What time period(s) does the Iliad represent? These are all important questions, depending on what you want the students to get out of the class. However, these questions could also take up several months of class time, if not an entire semester. Do you sacrifice breadth or depth? Where does writing instruction fit in?

That’s a wordy way of saying that teaching the same content in two different types of class taught me the sorts of questions that matter when thinking about course planning, and it made me much more conscious of the different focuses that a course can have, which leads me to my next point…

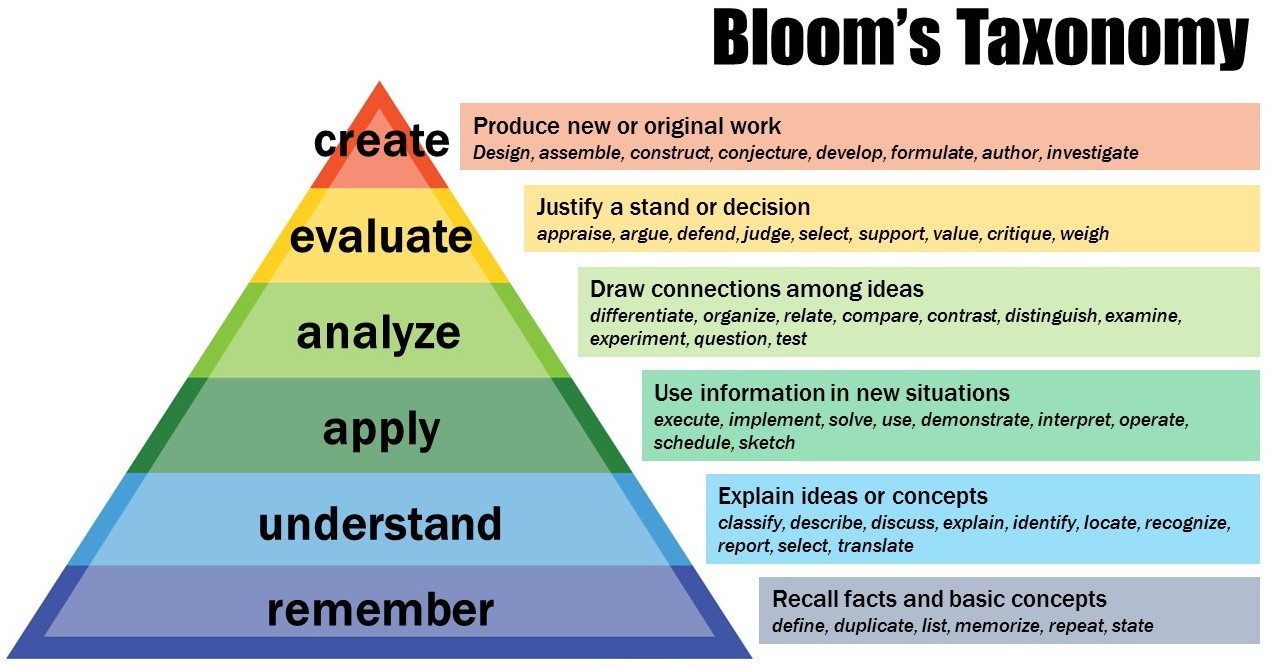

Learning Objectives: To be honest, when I first started teaching at Michigan, I thought a lot of the pedagogical talk about “learning objectives” and “scaffolding” was a little unnecessary–after all, if you’re teaching the content effectively, why did it matter if you’d designed a class forward or backward? It felt to me like these things were jargon and were over-theorizing teaching to the detriment of the course and the students. I have since changed my tune, and one place where I particularly appreciate a theoretical framework for thinking about teaching is in terms of learning objectives. In terms of Bloom’s Learning Objectives

Teaching Great Books, in which there were no exams and the students’ grades were based entirely on writing assignments and section attendance/participation, I noticed immediately how a course changed when learning objectives changed. Without exams that asked students to produce specific facts, some of the details and specifics became less important (the remember level of the pyramid), and we were able to spend more time on some of the higher levels of the pyramid, such as analyze and evaluate. In a discussion section, if my students were deeply engaged in a particular passage of the text, we could dwell on that passage for the whole class, rather than feeling as though we needed to cover all of the reading. In CC101, the students were tested on things like basic Greek geography and history, which meant we needed to cover those topics in discussion sections. With a finite amount of time, that necessarily meant more breadth and less depth in discussions.

The benefit of the Great Books-style course is that the students do get a lot more practice at close reading and argumentation. I found my students wrote far better essays in Great Books than they did in CC101, simply because we had time to model the entire essay-writing process in class. I could structure one day’s class around close readings of two passages and ask the students to analyze the passages and then form some sort of argument based on the two passages. Then we could raise objections to that argument, discuss how their central argument might change to accommodate points they had not initially considered, and then we could revise our thesis statement accordingly. Even if we were not discussing a passage that was at all relevant to their own essays, a single class session could model large swaths of the writing process for the students, so that when they went to write their own essays, they were already familiar with the process and with the sorts of questions they should be asking along the way.

The downside is that I am certain that many of my students could not date many of the texts we read in that course to within a century. They might not all be able to locate Greece on a map. My CC101 students certainly could. They had opinions about whether there was an actual Trojan War. They could place Athens, Sparta, and Corinth on a map. As a Classicist and an educator, it is hard to say that one option is better than the other, in a vacuum. What this did teach me, however, was how learning objectives really do drive course planning. I have grudgingly made peace with the fact that I cannot teach everything in a given class, and these similar yet different teaching experiences have helped me think through what is gained and lost in each type of course and how courses and assignments can be arranged in order to maximize a specific learning objective or two. Rather than trying to accomplish everything in one semester, this experience has taught me to be more selective with my learning objectives and do fewer things but do them very well.

As a final note, Great Books was the last class I taught at the University of Michigan (Fall 2015) and it represents the culmination of my teaching career. I include here comments from my teaching evaluations in that final term, since they reflect several years of commitment to improving my teaching:

Our discussion section was very helpful for doing well in the course overall. Amy was always very approachable and prepared for class, and gave clear expectations as well as giving students information about what was going to be discussed in the next section. Discussion was significantly more helpful…in understanding the thematic connections based upon the summary and analysis by connecting themes back to other books and the course in general.

Amy was very approachable and made sure that we knew the deadlines for our assignments. Discussions were very friendly and we knew what was expected of us. She gave her input on the texts and made sure to incorporate all of our ideas. Overall an amazing recitation!

Amy did a fantastic job facilitating discussion. Furthermore, she gave very constructive feedback on assignments and was always willing to meet with students outside of class if they wanted additional help.

I thought Amy was a great instructor. She is very organized and prepared, which makes discussion run smooth. She is also very approachable and always willing to help when you need it.

Loved Amy, I only have positive regard for her. Everything about that class was good, and the only real drawback is the fact that it is at 9 AM. I enjoyed Amy’s lessons, and enjoyed the class!

I loved having Amy as a GSI!!! Even though 9am was a rough class to be in, she always had a lot to say and had things planned for class. Though her emails were frequent and lengthily, they always left me feeling prepared for class or my assignments the next day. Amy was super approachable; I always felt like I could email her or come to office hours to ask for help or talk about anything. She really related to us as teenagers, using examples we got and lingo that made class funny and interesting.