You can find a lot more information at GamefulPedagogy.com, and a lot of what I’m drawing on is taken in all or part from there. To start, here’s how they gameful learning:

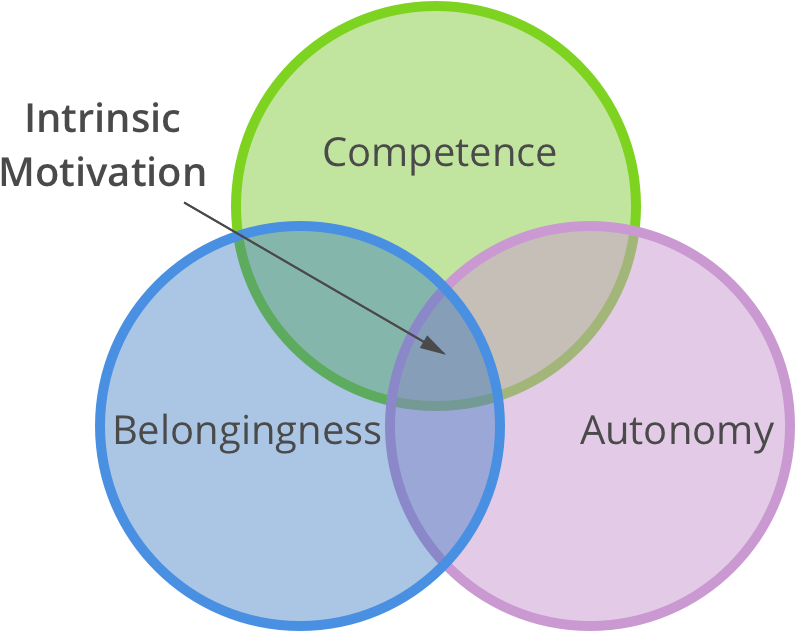

Gameful learning is a pedagogical approach that takes inspiration from how good games function, and applies that to the design of learning environments. Gameful design operates in a self-deterministic framework–we want to apply what self-determination theory says about how intrinsic motivation works to build motivating classroom experiences.

This concept of intrinsic motivation is something that undergirds a lot of good course and assignment design. I first read about it in Cheating Lessons, where James Lang talks about how intrinsic motivation drastically decreases cheating (I live-tweeted reading the book, in case you’re interested). As he points out, a grade (or at least a grade alone) is external motivation. If the grade is the only motivation they have for doing your assignment, the learning is more likely to be shallow and short-term. They aren’t invested in what they’re doing. Maybe this comes from the fact that they’re taking a class for a requirement or taking it pass/fail. Sometimes (hopefully less commonly, though this is what Lang is most concerned with) it comes from a sense that we aren’t invested in the class and so why should they bother caring if we don’t?

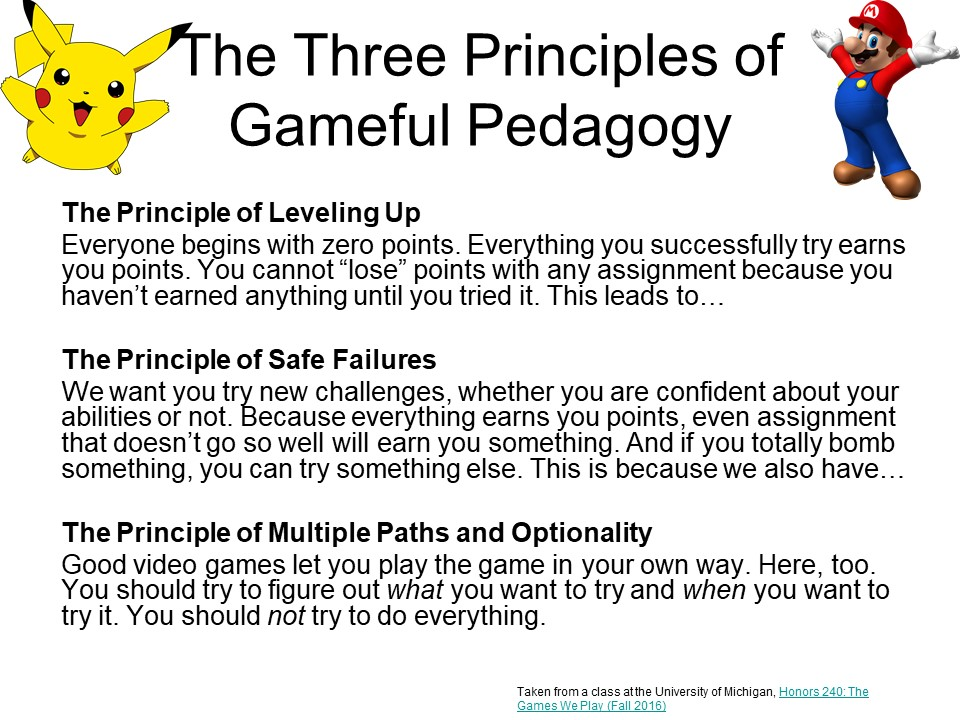

So how does this tie into gameful pedagogy? Why thank you for asking! These are three principles of gameful pedagogy that I stole from Professor Tim McKay’s course, offered at the University of Michigan, that really encapsulate what I saw in this sort of class design:

Leveling up

We start classes with an implicit assumption that everyone has a 100% before the class starts. The unfortunate implication of this is that each assignment is a chance for students to lose points. The longer the course goes on (and, by extension, the more the students learn) the more points the students can lose. That’s a terrible way for students to approach learning, in constant fear that their next assignment will be the one that drops their grade out of the A range. By contrast, a gameful design means that students start with zero points and each assignment is an opportunity to earn positive points. Which leads nicely to the next principle…

The Principle of Safe Failures

Since students start with no points, they have nothing to lose by trying something, even if they aren’t necessarily good at it. A failure isn’t catastrophic and — perhaps more importantly — it’s clear to students that it isn’t catastrophic.

A test where a student gets 60% of the questions right is, traditionally, an F. Seeing a big F on a test is going to be traumatic for most students, and rightly so. They’ve been trained for 12+ years of school that an F is the worst thing they can do. It’s failure, and no one wants to be a failure.

An assignment where a student receives 21 out of an available 35 points is still 60%, but it’s substantially less shocking and scary for our students. It still tells us as instructors (and the students) that they have some more work to do on that material. But it makes the experience less discouraging for students and (I think) helps remind them that a temporary failure isn’t the end of the world.

The Principle of Multiple Paths and Optionality

In part, this gets back to the idea of intrinsic motivation. If students have choices about which assignments they’ll do, they feel more a sense of ownership about the work they’re doing. It minimizes the amount of times students will be doing work they hate doing (it’s not going to eliminate it — no one likes memorizing irregular verb forms), which also means that students will by and large be doing better work.

The other great perk of this is that it gives students a lot more control over their schedules and workload. If they don’t have to do every single assignment, they can skip an assignment when they have a lot of other stuff going on, either in life or in other classes. This codifies the sort of flexibility that a lot of us want to be able to give our students.

So, what does it mean to actually design and run a class like this? I’ve only done it once (you can read about that here), so I’m far from an expert, but as I’m preparing to try it a second time, I’m struck by how different this class can look from the one I taught before. The idea of a gamified course doesn’t limit what you can assign and what you can require. There are platforms that can help with the logistical work (GradeCraft is the one that I’ve used, but there are a lot of other options out there), or you can just add elements that are drawn from this kind of an approach to a more traditionally designed class. I’m still planning to play around with this idea (and document my process), but thus far I am a big fan and proponent of the mindset and pedagogical approaches that gamification promotes!

no replies